by Diana Alvarez

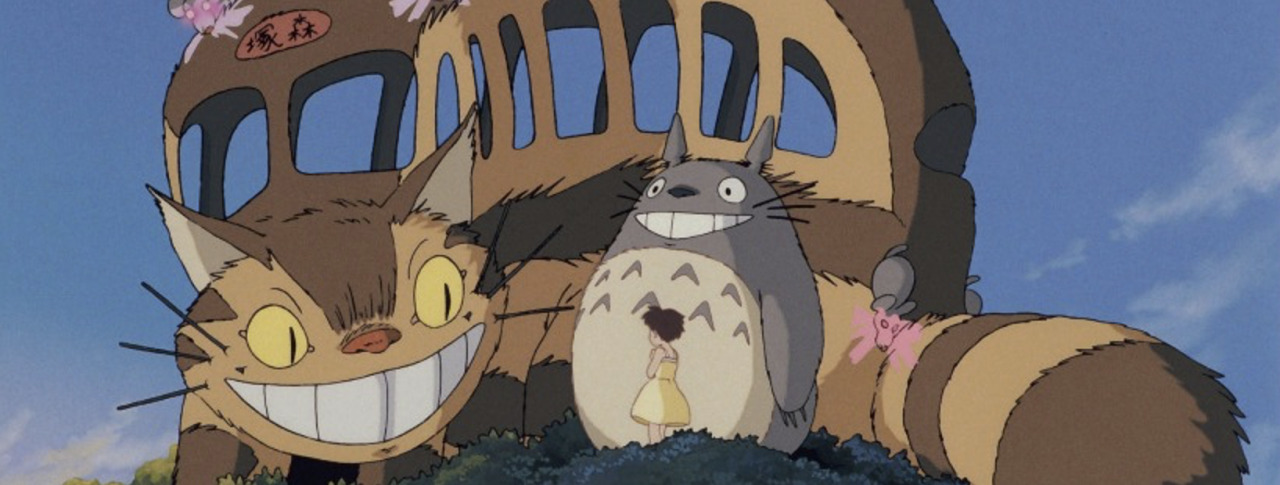

When walking into the Academy Museum’s entrance for its Hayao Miyazaki exhibit, we are taken through a green passageway, much like the one young Satsuki and Mei take to cross into the forest spirit’s world in the film My Neighbor Totoro. As we walk through this tunnel, it becomes a sensory journey of sorts that is enhanced by Joe Hisaishi’s soundtrack for the film, vivid storyboard art, as well as projected scenes of Miyazaki’s many animated films. We are immediately immersed into the animated universe the director has constructed throughout his career. Each visitor is taken on their own unique journey based on their personal background and experiences as well as their familiarity with Miyazaki’s work. It was both my visit to this exhibit and rewatching the film My Neighbor Totoro that urged me to look inwards, taking me on an emotional journey from which I was able to examine the losses I (as well as so many others) have recently undergone.

I’ve always found myself intrigued by the dystopian genre and how it touches on global catastrophe, but it is one thing to read about and another to witness firsthand. It is bizarre (for lack of a better word) to think that we have—and we continue to be in the midst of what could be referred to as a pandemic apocalypse. The last two years feel like they have taken an eternity. And somehow, when I look back, the last two years also feel like they have flown by. During this time, I have experienced both victories and losses, which have ultimately been transformative experiences. However, I have a hard time finding a balance between what I can celebrate and what I can mourn. In Joe Pinsker’s The Atlantic article “All the Things We Have to Mourn Now”, he attributes this to “the turmoil of the pandemic [as] altering and interrupting the normal course of mourning.”

In these last two years, I transferred to CSUN (after years of starting over at a community college because I’d been academically disqualified from another state university). I dealt with the sudden full-time shift into virtual learning. I qualified for financial aid for the first time in my life. My paternal grandmother developed sudden hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. I found myself dealing with our convoluted healthcare system in trying to advocate for her health. I was on the Dean’s List for three semesters in a row. I was part of a pilot peer mentor program at my university. I wasn’t able to see my close friends. I wasn’t able to see my boyfriend. Because I live with my paternal grandparents, I thought it best to stay at home and avoid physical contact with anyone outside of my household. I felt the weight of the world on my shoulders because I believed I was responsible for the health of my family to such an extent that it took a great toll on my mental health. One of the hardest losses, however, was the passing of my maternal grandmother, Genoveva Capcha, and seeing how it affected my mother. Yet despite that, it is during these last two years that I have cultivated a stronger relationship with my mother and gotten to know her better.

When I rewatched My Neighbor Totoro, I was stunned at the connections I observed between the film and my own personal life. The film resonated with me in a way it never had before.

My Neighbor Totoro takes place in a Japan previous to massive industrialization. The film’s premise is pretty straightforward: sisters Satsuki and Mei move into the countryside with their father as the mother remains in a sanatorium close by due to an illness that is never quite disclosed. The little girls make the best of their situation by finding the wonder in their natural surroundings. They befriend Totoro, a forest spirit, and cross into an imaginary world that soothes them from harsh realities we wouldn’t wish on any child. According to Susan Napier’s book Miyazakiworld, the film “reconstructs [Miyazaki’s] boyhood, processing youthful dreams, and nightmares to offer a magical world of protection, nurturing, and resilience” (107). The film explores what it means to undergo personal and universal losses. When we consider our current reality, many of us feel responsible for the consequences of massive economic and industrial expansion. We feel it because we have been the ones to pay the price. During this pandemic, we have witnessed governments prioritize business over human lives. We have witnessed the politicization of a public health crisis that has led to further division. We have lost more than six million lives worldwide due to COVID-19 complications.

And yet, we have found ways to cope with these years of uncertainty in a way that is comparable to the sisters in My Neighbor Totoro. Some of us have worked from home. Some of us have been unemployed. Some of us have found refuge in our natural surroundings whether it’s been by going on a walk or taking a trip beyond our urban landscape.

In Kosuke Fujiki’s essay, “My Neighbor Totoro: The Healing of Nature, the Nature of Healing”, he discusses the significance of the pastoral landscape and its influence over the film’s characters. He asserts, “the film’s portrayal of 1950s village life in harmony with nature [is] nostalgic or even utopian for [those] who [are] no longer in contact with natural landscapes in everyday life” (Kosuke 156). Nature has long been associated with the power to soothe and heal us. It is my belief that nature did just that for my abuelita in the last two years of her life. As a result of the pandemic, her children and grandchildren came to stay with her in the countryside. She was able to enjoy the innocent liveliness of her grandchildren. It’s a beautiful thing to be able to spend time with your family especially when one’s sons and daughters have grown up and moved on to form their own families. In a sense, it was the pandemic that brought my abuelita’s family back to her. I’m very thankful for that.

Although the mother’s illness in My Neighbor Totoro is never explained, there has been a lot of speculation that it is tuberculosis. Miyazaki’s own mother had it too. The film “incorporates an absent mother, the gloom of her possible death, and even the dramatic move from town to countryside” (Napier 111). The uncertainty of one’s health creates a state of limbo because of how it alters our ability to mourn. Although everyone has their own grieving process, “human beings need to see the body of our loved one, to have remains, in order to know that our loved one has been transformed…So even many clear-cut losses have become ambiguous—unclear and lacking resolution” (Pinsker). In the case of my abuelita, she developed pulmonary fibrosis and it was further complicated because of her tuberculosis. It is our belief that she got tuberculosis from visiting a sick family friend at the hospital. She went from having healthy lungs to needing a portable oxygen concentrator to eventually needing oxygen 24/7.

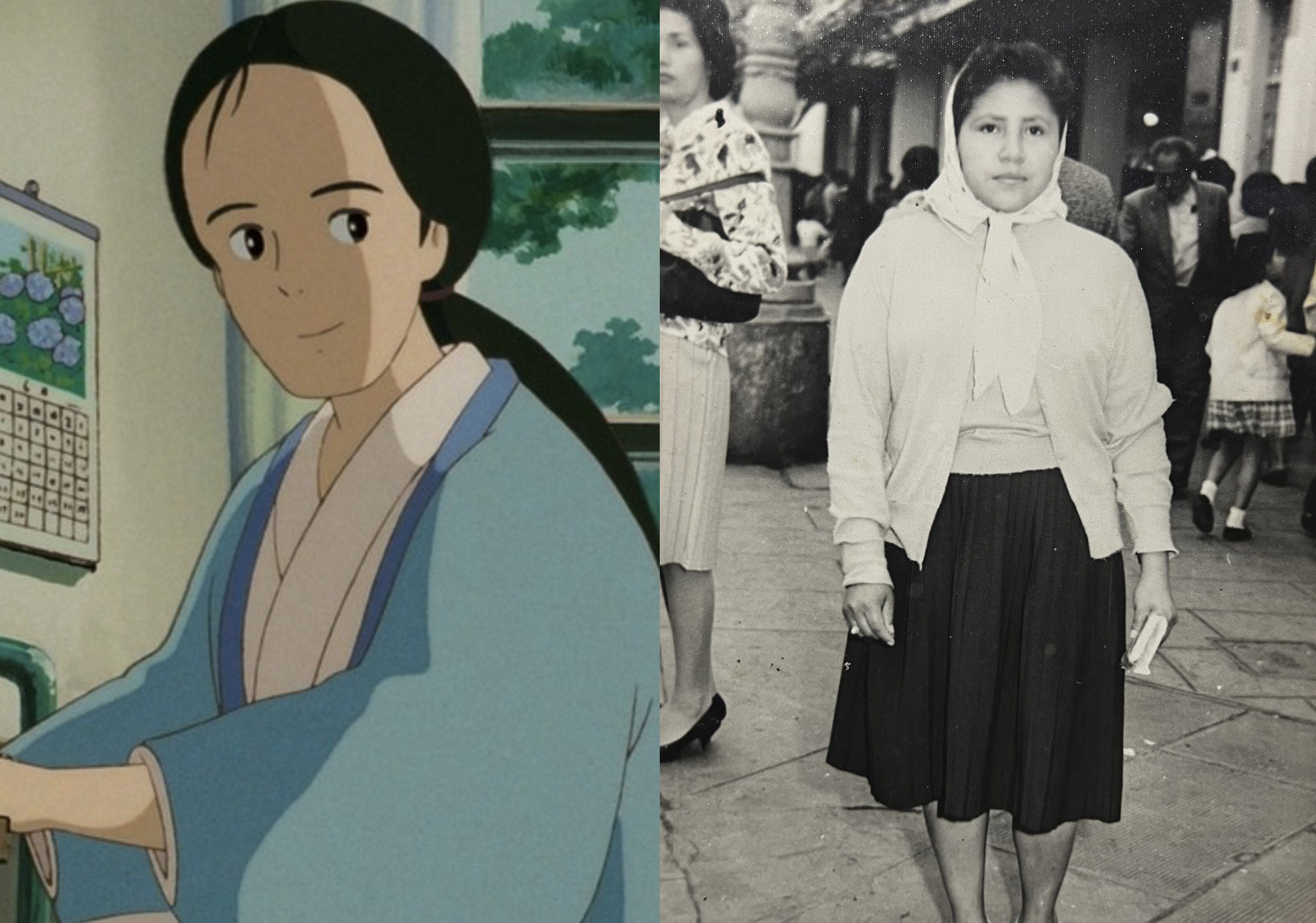

Throughout the film, the mother makes few on-screen appearances, but she is a driving force for her husband as well as her daughters. The mother, Yasuko, is depicted as a warm and perceptive figure. We see her comb her daughter’s hair and listen intently to the stories her family has for her. She demonstrates a silent strength despite her illness so to not worry her family who has already sacrificed so much for her. In contrast, my abuelita Genoveva was a strong and hard-working woman who was rarely sick. Her strength was not silent. She was one of those tough grandmothers who never wanted to be fretted over. If anything, she was the one to fret over us getting up early or if we’d fed the animals on her farm. She had a different way of expressing her love and concern for us.

Because of the strength we all knew and admired her for, it was extremely difficult for me and my family to see her state of health suddenly deteriorate. She fought against it to the very end. I remember how she’d wait for us to turn away so she could walk down her farm and go see her grandchildren. I remember how she scolded my mother and I because she thought we were hovering over her too much. I remember how our conversations got shorter with each visit I made, but the smile on her face when we’d first arrive remained the same. I was thankfully able to visit three times in the last six months of her life.

In sickness, my abuelita became a driving force that brought all her family together. COVID-19 cases went down in California. In the last year of my abuelita’s life, my mother was able to make several visits whether it was with us or on her own. She was able to spend time alongside her mother and siblings, creating memories for the many years she had missed out on.

When my mother was pregnant with me, she made the difficult decision of leaving her family behind for more opportunities in the U.S. She wouldn’t be able to return to her birth country for more than twenty-two years. She maintained contact through telephone and written letters with pictures of her new family. It is a tremendous sacrifice that I do not romanticize.

And somehow, it was my abuelita that gave back to her family by physically uniting everyone once more. She had always considered family to be sacred. The same effort she put into raising her children—she received from them. As her illness progressed more and more, her family remained by her side. In My Neighbor Totoro, Satsuki and Mei are only children and yet they put on a strong face to cope with the uncertain fate of their mother. Although my mother and her siblings are no longer children, they demonstrated a similar strength as the six of them created a schedule to make sure their mother Genoveva would always be taken care of. We were determined to never have her stay overnight in a hospital. She hated doctors. She loved her countryside and the dozens of avocado trees that were the fruit of her lifetime of labor. My family made sure to work the land for her when she no longer could.

(from left to right)

There’s a moment in the film in which Satsuki and Mei discover that their mother’s condition has worsened and she can no longer visit them in their new countryside home. Mei has faith in the restorative powers of nature and she becomes determined to take an ear of corn so that her mother will get better (Fujiki 153). Satsuki, the older sister, becomes flustered by the uncertainty of her mother’s condition and she can no longer maintain the charade. When Satsuki demonstrates the vulnerability that is natural for a child coping with the ongoing loss of a parental figure, it terrifies Mei. Satsuki “opens the floodgates to her own awareness of adult mortality, something that she had previously blocked by busily taking on the chores and persona of the adult child” (Napier 124). It is my belief that loss—particularly the loss of a parental figure—brings out the child in all of us. We can hold a strong face if we sense that our loved ones need it, but it is natural to be overwhelmed by the realization that loss is inevitable.

During the first year of the pandemic, I remember the crippling sensation from the uncertainty that loomed over the world. It was daunting to know that my own parents were just as uncertain as I was. I remember a late night in which I could see the concern on their face. They did not have the answers to this global pandemic and they were frustrated by the growing division in our country. My only way of coping was throwing myself into my studies, fiercely determined to get my bachelor’s degree if it was the last thing I did.

I was able to find refuge in literature and film. It would transport me to a different reality that I had control over. I had the freedom of being a distant observer and being distracted from my own reality. According to the Artwork Archive, “art reminds us that we are not alone and that we share a universal human experience. Through art, we feel deep emotions together and are able to process experiences, find connections, and create impact.” That is precisely what happened when I rewatched My Neighbor Totoro and visited the Hayao Miyazaki exhibit in the Academy Museum.

It is only fitting that the green passageway in the exhibit’s entrance links to the “Mother Tree” installation near the end. The installation reflects the interconnectedness between humans and nature that Miyazaki’s films urge us to reconsider.

In the end credits for My Neighbor Totoro, it is suggested that the mother recovers enough to visit her family’s countryside home. The film ends on an encouraging note. Whether our own sick loved ones come back to us or not, our memories with them will last a whole lifetime. Napier refers to this as “Totoro’s final magic…it allows us to recover what we have forgotten and to luxuriate in innocence, beauty, and joy if only for a few transitory moments” (124-125).

On the second visit, the night I was taking a flight back home, I went with my brother to say goodbye to my abuelita. It was the last time that I got to see her awake and conscious. I remember telling her that I’d try to come back one more time to see her and she nodded at me. By this point, she was bedridden. I had a sinking feeling in my stomach and wished I didn’t have to go back home. I wished my brother and I didn’t have to return to classes. My abuelita held onto her strength for as long as she could. When my father took a flight back home, my abuelita went into a deep sleep. It was as if she felt she didn’t have to pretend anymore.

And yet, my abuelita waited for us to fly back a third time. My mother had stayed behind and she called to let us know the nurse had said it was only a matter of days. We took a same-day flight and were hopeful that we’d be able to see her once more. Although my abuelita spent her last days in a deep slumber, I believe that she felt our presence. I remember holding her hand and talking to her, thanking her for everything she’d done for us. Even at the very end of her life, she remained fierce. The nurse had confidently told us it’d be a matter of hours and that she knew this because of her many years of experience. My abuelita had always been a proud woman and wanted things her way. True to her character, she defied the nurse’s words many hours later, passing at 5AM on a Sunday morning.

Grief is a strange thing in that it is a different experience for everyone. The wake and funeral service we held made it easier to both commemorate and mourn the loss of my abuelita Genoveva. However, providing end of life care for a loved one is hard because it feels like a loss that is ongoing. It is somewhat easier to let go at the end because you don’t want your loved one to suffer anymore. But for the same reason, you are trapped in a limbo state of mourning for as long as you see them suffer. I resonated with My Neighbor Totoro to the point of tears because I felt seen. The film felt like a warm blanket because it allowed me to feel like a child again, providing me the outlet I needed.

Although Miyazaki’s film takes place in 1950s Japan, its underlying theme of personal and universal loss continues to resonate today. By reflecting on my own connections to My Neighbor Totoro, it is my hope that it encourages others to visit the Academy Museum’s Hayao Miyazaki exhibit and form connections of their own. The exhibit’s last day will be on June 5, 2022 and tickets can be purchased in advance here.

As a final dedicatory note to my abuelita Genoveva, I’ve attached a song from Peru’s Banda Show Internacional Sunicancha that makes me think of her called “Madre” (mother).

Diana, grief is a strange thing indeed. Your abuelita Genoveva sounds like an amazing woman, a source of life and energy and strength. I am sorry to hear that she is gone, sorry for your loss, and grateful for thoughtfulness of your essay, which brought my own and my family’s losses over the past couple of years into sharp focus. I hope I can learn to remember my parents with the same openheartedness with which you memorialize your abuelita in this piece.

How fitting that you have brought together thoughts of the pandemic, and all our losses, with My Neighbor Totoro. You have reminded me of why I love this film.

I don’t often tear up when reading projects from my classes, but, well, this time I did. And I’ll remember Totoro differently, from now on.

PS. Thank you for including the family photos!

Diana,

I loved this. Thank you for your willingness to be so vulnerable and share some of what you’ve gone through recently, that takes a lot of strength. I love how you say your abuelita’s “strength was not silent,” it made me chuckle because it reminds me of my mom. I have a similar experience in that the past few years of my life have been uh, a doozy to say the least. I found myself working through a lot of grief this semester, which naturally drew me to the themes of loss in Miyazaki’s work, loss of any kind. That’s also why I wanted my group’s video essay to highlight how Miyazaki’s stories show us that loss is an inevitable part of life that we don’t just “get over” or “move on” from, it’s something we learn to live with. And despite that, we can still find joy and reasons worth living, amidst all the grief and loss and transience. This is definitely a really special piece of work, thank you for sharing! And for making me cry!

Diana,

I was so moved by your essay, I felt speechless and even teared up reading this. First, I want to say thank you. You’ve put into words what so many have felt during this pandemic. As well as being very open about your experience with grief, your perspective has brough insight into my experience and the process I went through after losing my mother. It’s not something most of us want to define in the moment but you’ve brought forth the clarity I’ve been trying to put into words for years now. Second, I love your observation about the mother tree from the Miyazaki exhibit. That was something I didn’t notice at first, but I resonate with your idea that we are all interconnected with nature and the people in our lives. Totoro reminded me of being young and exploring my own backyard as a child, we also had an avocado tree, my dad watched it like a hawk hoping for a harvest. Something I’ll cherish from that movie was the way we’ve all been able to see our younger selves in Satsuki and Mei. Your account of experiencing grief and being surrounded by the love and support of your family only adds to the movie’s tagline, “we are returning something you have forgotten.” This was a wonderful piece, excellent work!